Clarence Lee Shirrell gets a kiss from Miss C, the camel, while Stripes, the zebra, tries to grab a bite of hay at Shirrell’s former concrete statue business off I-55 in Missouri.

[This post is part of my Travel Tales series where I share personal stories from life on the road. This essay started as a graduate school class project. Two decades later, it’s time to share it with the world. ]

The first time I saw the camel was on a spring break road trip in 2005 as I was heading south on I-55 bound for Memphis. I was bored and reading billboards—the only scenery in rural southeast Missouri. Nestled between two gigantic billboards was a camel in a pen along a frontage road. I did a double take, pulled off the interstate at the next exit and backtracked to investigate. I wasn’t going to pass up the opportunity to potentially pet a camel.

The camel’s home was a concrete statue business surrounded by farmland. A black, cast-iron welcome sign with camel silhouettes leaned against a fence post by the entrance. A lone metal building stood in the center of a field of concrete—statues, planters, birdbaths and benches. An old man wearing a baseball hat was loading a giant giraffe statue onto a trailer behind a white pickup truck. He walked over to greet me, and I asked if I could pet the camel.

He pulled his wallet out of his back pocket and took out pictures of a baby camel as if it were his grandchild. Here was the day he got the camel in May 2003, he said. She was 10 days old and nothing but legs. You can tell she’s real wild, he said, pointing to a picture of the camel kissing him on the head.

Miss C was her name. “Miss because she’s female and C for camel,” he explained. “That way I wouldn’t forget her name.” His name was Clarence Lee Shirrell, and he was 79 years old.

A photograph of Miss C, the camel, through the shop window. Shirrell’s childhood friend told him Miss C would bring more customers than a billboard. And, he was right.

I started driving two hours out of my way just to visit Miss C and Mr. Shirrell on my road trips home to South Carolina during school breaks. I spent countless hours photographing and talking with him for a project for my photojournalism class. We became good friends despite our 55-year age gap.

When I told him I decided to title the project “The Old Man and the Camel,” I was worried he’d be offended, but he just laughed and said it was a good title. His laughter was my blessing—I would always refer to him as the old man and the camel to my family and friends.

There were new animals every time I stopped to visit. Each one had a name—a pair of emus, Jack and Jill; Bob, the anti-social peacock; and Snowball, a fluffy white guard dog who kept the coyotes away.

Snowball, the guard dog, watched over the other animals.

During a January visit, I walked inside the metal building that served as a workshop to say hello and met the zebra for the first time. “Did you ever see a prettier striped mule?” he said, joking about the three-month-old baby zebra. “He’s a Grant’s zebra, and that’s why we call him Ulysses.”

He bought Ulysses in Louisiana and brought him home in the front seat of his pickup truck because it was too cold for him to ride in the trailer.

Ulysses was content inside by the woodstove, but once the weather warmed up, he’d have his own large pen by the interstate like Miss C. It’d help business, he said. The animals were his advertising. Curious passersby, like me, always stopped to investigate.

One afternoon, I wandered around outside photographing the animals. The old man was smoothing the edges of a concrete angel when I went back inside to say goodbye.

When Ulysses, the zebra, nibbles on a piece of concrete while Shirrell set out some hay. The baby zebra lived indoors her first winter until it was warm enough for her to move outdoors.

When Ulysses, the zebra, nibbles on a piece of concrete while Shirrell set out some hay. The baby zebra lived indoors her first winter until it was warm enough for her to move outdoors.

The interior was a large open space with windows facing the interstate. A picture of the zebra in the front seat of his truck sat on top of the desk by a window. More pictures of the animals were stacked high on the corner for visitors to see. An empty black chair sat facing his workbench as if he were expecting company.

“Sit down for a minute if you can,” he said. I smiled and sat in the chair between the workbench, the woodstove and the zebra that was munching on some hay.

A baseball hat with plastic netting on the back shaded his gentle blue eyes. The same kind of hat my granddad used to wear. I’d rarely seen either without a hat.

I tell him that I think I’m getting old at 24.

“I don’t have a problem with getting old,” he says. “Because it means I didn’t die young.” He had a good point, but it’s hard for any mid-20 something to comprehend that getting old isn’t a bad thing.

Missouri native Clarence Lee Shirrell smooths the edges of a statue of an angel inside his workshop near Cape Girardeau.

Often, I’d hop in his white pickup truck, and we’d drive over the interstate to the small hamlet of Fruitland for lunch at a hole-in-the-wall buffet restaurant that baked bread in flowerpots and had the only good sweet tea in Missouri.

Our conversations often revolved around our families. He’d lived in southeast Missouri his entire life except for a two-year stint in the army. He worked at his father’s concrete business before starting his own in 1981, the same year his first wife died of breast cancer after 32 years of marriage. He remarried on Valentine’s Day eight years later to his current wife, Donna, who is nearly 20 years younger. He still goes to lunch regularly with his high school friend, Lon Maxey, and I was lucky enough to join them on one occasion.

Lon—who founded a sign and billboard business—is the reason the old man got the camel in the first place. Lon had assured him the camel would bring in more business than a billboard ever would, and he was right.

“I’ve been very blessed being able to do something I enjoy very much,” he explained once.

He enjoyed hearing about my dad who shares the same love for his unique job—handcrafting 18th century furniture. He, like my dad, supported my unconventional dream to be a globetrotting freelance photographer.

Graduation ended my visits to the old man and the camel after almost two years. My parents drove to Missouri for my graduation, and I made them take the same two-hour detour to meet my friend. His wife was graduating with her Ph.D. the same day we were visiting, so we tried to arrive before he left for the ceremony. Our departure was delayed, and we missed him by an hour. Disappointed, I took photos of my parents, sister and four-year-old nephew with the camel and mailed them to him.

My mom took a photo of my sister (far left), me, my nephew and dad posing with the camel on our visit after our graduation.

My mom took a photo of my sister (far left), me, my nephew and dad posing with the camel on our visit after our graduation.

I moved south to Alabama for an internship that eventually led to a successful freelance career. We kept in touch through cards and letters. I told him about my jobs, travels and even mailed him copies of my published magazine stories. He sent me updates and photos of the new animals and statues. I almost cried the day I heard Ulysses, the zebra, died. Every time, I’d see his cursive handwriting on a card in my mailbox, I couldn’t help but smile.

When the failing 2008 economy threatened my freelance career, I took the opportunity to follow another dream and spent 13 months living in Australia and Southeast Asia. I sent him postcards from every place I visited.

A week before I moved back to the U.S., I sent one from Australia telling him I would be stateside by the time he got it. Shortly after I returned home, a card arrived in the mail with familiar cursive handwriting and a Missouri postmark. “Hope your travels bring you up this way,” he said.

I will always remember a visit after Christmas break in early 2006. A quick 30-minute stop turned into two and a half hours.

The sky was growing dark outside, and I still had three hours left to drive back to school in Columbia. I reluctantly said goodbye to my friend and the camel.

“Have a great weekend,” I said.

“You made it better just by stopping by,” he assured me. I smiled for the next thirty miles because I felt exactly the same. He never ceased to make me smile, even just the sight of his squiggly handwriting in my mailbox would make me grin.

On my last visit in 2013, Shirrell introduced me to Stripes, the zebra.

On my last visit in 2013, Shirrell introduced me to Stripes, the zebra.

When I moved to Southern California from Alabama in 2013, I purposely planned my cross-country route through Missouri just to visit the old man and the camel for the first time in six years. He was sporting a new mustache and was dressed up in a light blue fedora, brown jacket, tan button-down shirt and jeans. I was dabbling in video at the time and recorded a short series of interview clips with him and his painter, Christa, about the business with the intention of making them into a video project that never came to fruition. He had sold the business to Christa and was working for her part-time.

He introduced me to his new zebra, Stripes, and took him for a walk around the property with a stop by the camel’s pen where Miss C bent over to nuzzle his face in a moment of affection that made it clear how much they cared for each other.

Leaving our visits still had the same effect on me. I’d reluctantly get on the interstate and smile for miles.

I quickly learned that California wasn’t for me and moved to Texas the next spring, which became my home base and the place where my career skyrocketed. It took a lot longer than my 24-year-old self would have liked, but I earned bylines and photo credits in the big-name publications I always dreamed about.

As we continued to exchange cards and letters, his handwriting was getting messier and harder to read. His wife, Donna, started writing the cards for him, and I’d look forward to seeing her neat script in my mailbox. Due to my frequent travels and seven address changes, I instructed them to send everything to my parents to ensure nothing was lost in my many moves. My mom would email me and say, “You got a card from Mr. Shirrell.” I’d call her and have her read the card over the phone.

In May 2024, the card I dreaded arrived in the mailbox. I was in Malta on holiday with a friend when I got my mom’s email. Mr. Shirrell had passed away the previous month at age 97. Donna said he loved me like a daughter. He had kept all my cards and letters and read through them often. And, I cried just like I’m crying now as I type this because I loved him like a grandfather.

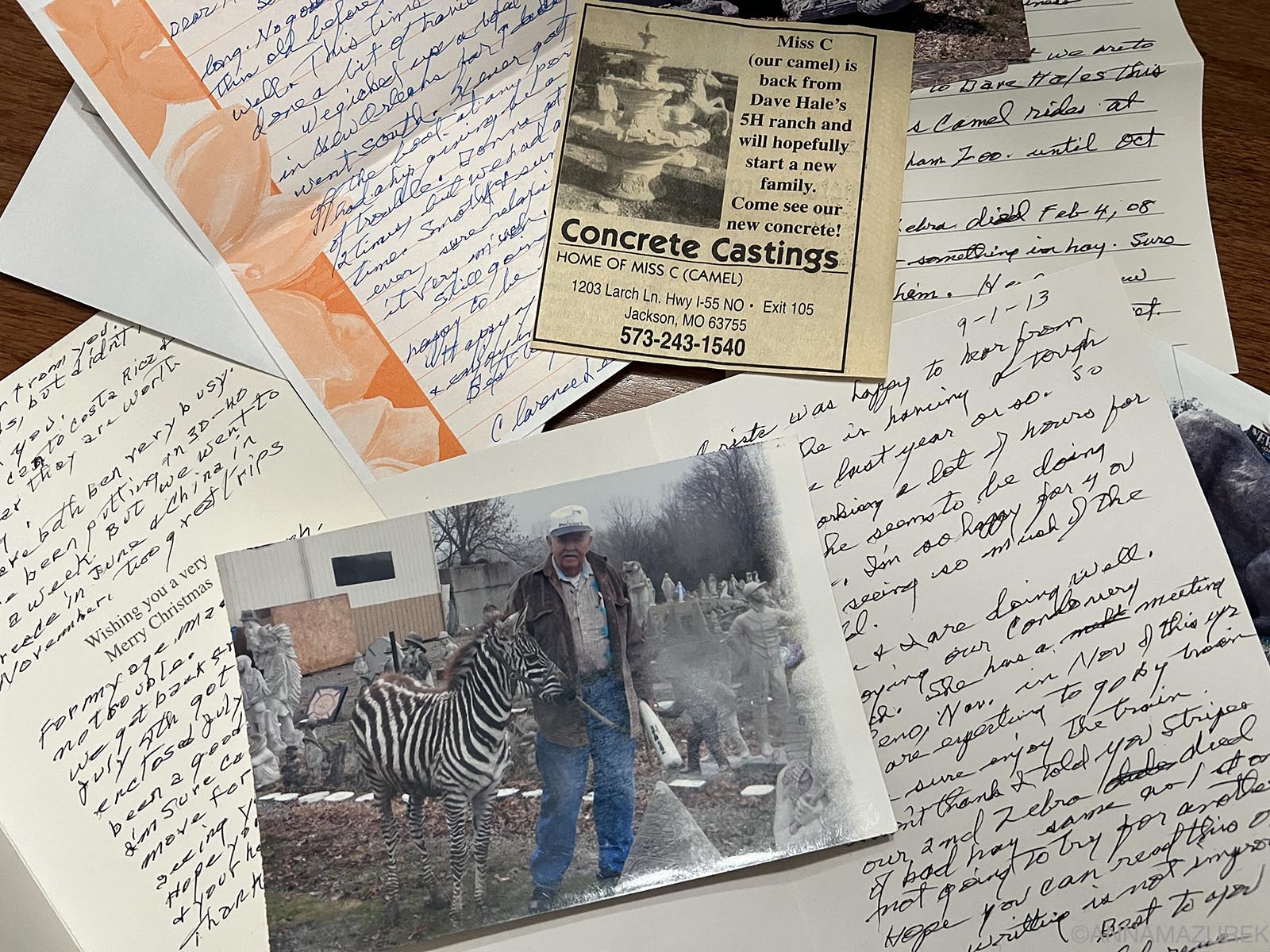

When I visited my parents a month later, I opened my closet and pulled out an old Converse shoebox house with the words “old man and camel” scribbled in a black Sharpie on the front. I pulled out his cards and spread them across the hardwood floor of my childhood bedroom.

I saved every card, photo and letter Clarence Lee Shirrell sent me over our 19-year friendship.

I saved every card, photo and letter Clarence Lee Shirrell sent me over our 19-year friendship.

There were photos of the animals and a giant alligator statue. A homemade Christmas card with a photo of Miss C and a newspaper clipping announcing that she was back from a local ranch where she was bred in hopes she’d have a little baby soon. There were postcards from Greece and China—he and Donna were also travelers, taking cruises around the world. His squiggly script talked of adventures and new animals including ze-donks (zebra-donkey crossbreeds), chickens, ducks and several goats.

I started gathering the digital photo files of the old man to send to his family and made a few prints to send to Donna. I printed an extra copy of my favorite image, a portrait of him with the zebra to hang on the bulletin board by my desk.

In my card to Donna, I enclosed a few prints, and I asked if I could email her the digital files and video clips for the family. After we exchanged a few emails, I asked if I could still send her letters and postcards. I thought the old man would like that.

As I gathered up the 19 years of letters spread across my floor and put them back in the shoebox, I was flooded by nostalgia of our visits and my grad school road trips home. He was always glad to see me. I was always glad to see him. He taught me that getting old isn’t a thing to be feared and that friends can be found in the most unusual places. Most of all, I was grateful I stopped to pet the camel.